Living other people’s lives is no match for living your own

– Andrew Matthews

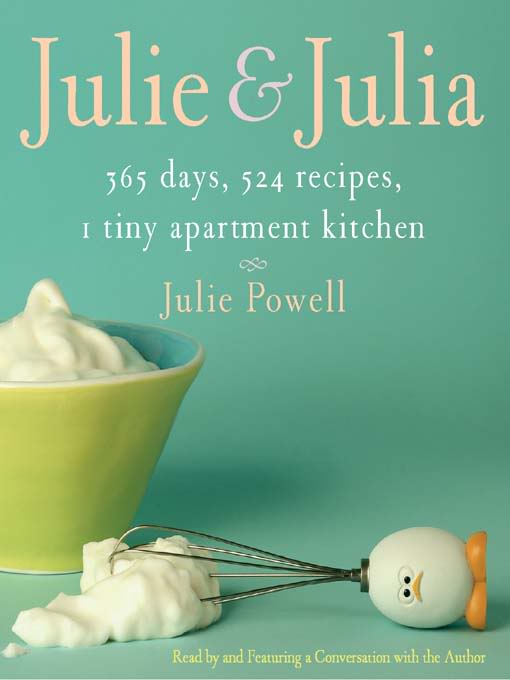

This week, the kids rented the movie Julie & Julia and we sat and watched it as a family. Ronit and I had seen it in a cinema and thought they would like it, if only because lately, they have been following some cooking shows on TV and spending more time in the kitchen (it is now Summer Break in Australia and school only starts in a few days).

This week, the kids rented the movie Julie & Julia and we sat and watched it as a family. Ronit and I had seen it in a cinema and thought they would like it, if only because lately, they have been following some cooking shows on TV and spending more time in the kitchen (it is now Summer Break in Australia and school only starts in a few days).

Now, there are two kinds of movie watches: those who hate to watch movies more than once (“I’ve seen it already, so what’s the point?”) and those who like it (“I already know it’s good, so it should be fun”). Kids are typically the second kind and can watch the same movies over and over again. Me too…

As it happens often when I watch a movie the second time around, I end up seeing a completely different movie from the first time. When the movie is new, most of our attention is spent on figuring out the plot, getting to know the characters and admiring the way the movie was made – music, special effects, camera work, etc. The second time around, we already know all this stuff and we can really dig deep into the nuances in the dialog, the hidden messages and, well, the glitches and the hints to other movies.

So as we watched Julie & Julia, I realized just how well the movie captures the great value of setting goals and the characteristics of successful goal setting. I was so impressed I made it a point to describe these things to my kids on our daily walks together.

At the beginning of the film, Julie is aimless and famously has the self-image of someone who never finishes anything. Changing herself is a monumental challenge, which is why she must commit herself in such a way she can never back out. It is finish or bust this time.

Here is what she does:

- Decide to change – she decides to take on a hard task and finish it with the specific intent of proving to herself and everyone else that she can do it. Goal setting needs a reason and Julie states it aloud.

- Take responsibility – Julie’s does not try to change anyone else and does not expect anyone else to do anything for her to change. This is her journey and she picks a challenge that depends solely on her.

- Choose a role model – because she likes to cook and admires Julia Child, she decides to follow in Julia’s footsteps and become a person she could admire. Goals are vehicles for emotional change. By knowing her desired emotional state (to be strong and confident like Julia), Julie sets an implicit (subconscious) emotional goal for herself.

- Set a deadline – by her own admission, this is necessary to avoid slacking and ensure completion, so she makes her mind up to achieve her goal within 1 year.

- Define milestones – in order to cook her way through the book, Julie would have to do some tough things – kill a lobster, poach (and eat) an egg and bone a duck. Each of them is a small achievement by itself, after which Julie would pat herself on the back and have a sense of partial completion. Milestones help to break a large goal down into “chewable chunks” (pun intended).

- Make the goal specific – Julia’s book contains 524 recipes, split into sections. There can be no mistake, because they are all listed right there. The achievement is very well defined.

- Pick action steps – each recipe is a step towards completing the goal. Each step would stretch Julie a little more by throwing a new challenge at her and requiring her to take yet another step. Each step would take a little bit of effort, but together they would add up to a big achievement. After each step, Julie would be able to “put a tick in the box” and feel good about herself.

- Make a public commitment – Julie lets her husband, mother and friends know about her goal, but then she goes a step further and decides to write a blog about her journey. This means that everyone out there would potentially hold her accountable.

- Gather support – apart from her mother, all the above also support her by eating her dishes, complimenting her, cheering her on, commenting on the blog, etc. Making changes in life is not easy and support is crucial. Julie’s husband, personal friend and friendly colleague are always there for her, either in a strongly positive way or in a way that gives her perspective (like when her husband leaves and her girlfriend agrees she was a bitch).

- Write a journal of success – one of the main ways to monitor progress and allow reflection is writing a journal. Julie’s blog is a great way to document her daily struggles and victories.

The difficulty kids have with goal setting is their short life experience. Without knowing enough about cause and effect, kids focus on having fun right now. Spending any amount of effort on a reward they may or may not get in the future is just not something they do.

Mischel’s original conclusion was that older kids can wait longer and deferred gratification is related to age. However, years later, he followed up with some of the children in his experiment and discovered that those who waited longer were also more successful in life.

In 1988, Mischel found that “preschool children who delayed gratification longer in the self-imposed delay paradigm were described more than 10 years later by their parents as adolescents who were significantly more competent”. In 1990, he found a correlation between the ability to delay gratification and higher Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores.

This is where we (parents) come in.

How to teach your kids goal setting

- Be the change you want to see in your kids – set goals and achieve them yourself (see above for some pointers).

- Set family goals – pick some things you can do together with the kids for mutual benefit, like doing a big cleanup in the garden, planning and preparing for a big camping trip or finishing a big jigsaw puzzle. Give each child at least one task to complete on their own.

- Suggest setting a goal for any project your kids want to do. This will leverage their existing motivation and help them think that goal setting is a great way to get what they want in life.

- Follow up, encourage, advise, help adjust, but never nag. As soon as you nag, you own the goal and you will never be able to give it back. Keep the tone at “How can I help you?” This point can be tough, I know, but it is absolutely critical. When kids learn the connection between their actions and their results, they gain something far more valuable than any good score on any assignment.

- It may take more than one attempt to get your kids used to setting goals, especially when they are very young. This just makes teaching this lesson a long term goal from your point of view, but it is still better done than given up.

Completing a goal gives a great feeling of achievement, growth and fulfillment and builds confidence like nothing else does. Self-confidence, in turn, makes it easier to achieve more goals, feel even better and build even more confidence.

Through the completion of her goal, Julie Powell became famous, got her dream career and found out that living your own life is more exciting and more fulfilling that living anyone else’s (namely Julia Child). May you and your kids experience the same.

Happy parenting,

Gal